Fact Sheet

Low-Achieving and Violent Public Schools in Pennsylvania

Overview

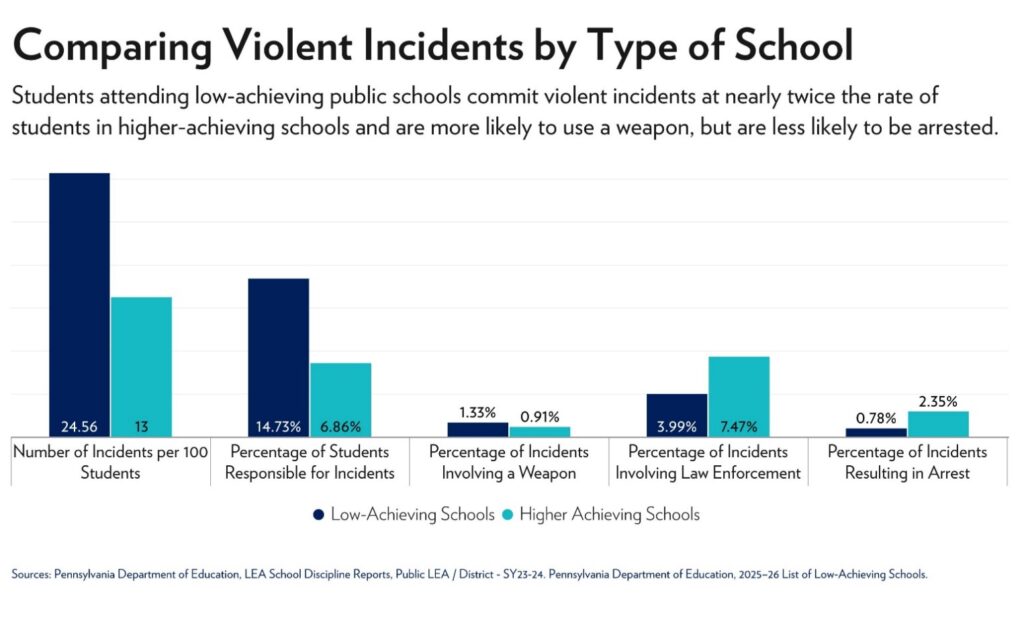

Students attending low-achieving public schools experience violence at nearly twice the rate of students attending higher-achieving schools and are more likely to experience violence involving a weapon.

Previous research shows that Pennsylvania defies state and federal law by failing to identify any persistently dangerous schools and neglecting to provide safe school choice alternatives for students who are victims of crime and/or attending dangerous schools.

Key Points

- Federal and state laws require the appropriate identification of persistently dangerous public schools and mandate offering students in these schools the opportunity to enroll in a safe school within their local or neighboring school district.

- There are 383 low-achieving schools in the commonwealth as identified by the Pennsylvania Department of Education (PDE) based on Keystone and Pennsylvania System of School Assessment (PSSA) standardized test scores.[1]

- Students attending low-achieving public schools experience violent incidents at nearly twice the rate of students attending higher-achieving schools.

- Students attending low-achieving schools are 68 percent more likely to experience an event involving a weapon than students attending higher-achieving schools.

- While criminal offenses at low-achieving schools are more prevalent and students experience more violence at school than their higher-achieving counterparts, a higher-achieving school is more likely to involve law enforcement and follow through with arrests than low-achieving schools.

The Persistently Dangerous Loophole

- The Commonwealth Foundation’s August analysis, “Persistently Dangerous Pennsylvania Public Schools,” points to the arrest loophole in calculating danger. Its findings—derived from Right to Know (RTK) data, a 24-year longitudinal study on school safety, news reports, and government data—reveal the ongoing neglect by school districts to report violence unless incidents result in arrests.[2] This practice ignores student safety.

- The 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and its several amendments, the last in 2015, place the responsibility of safe schools with the states and set educational accountability—including unsafe school choice option provisions—as requirements for federal funds.[3]

- Dangerous incidents at schools are what make schools unsafe, whether they result in arrests or not. The Pennsylvania Code defines a dangerous incident as:

- “A weapons possession incident resulting in arrest (guns, knives, or other weapons); or

- “A violent incident resulting in arrest (homicide, kidnapping, robbery, sexual offenses, and assault) as reported on the Violence and Weapons Possession Report (PDE-360).”[4]

- Pennsylvania designates a public elementary, secondary, or charter school as persistently dangerous by measuring the number of dangerous incidents within two or more of the respective school’s three preceding school years, but only for those that result in arrest.

- “For a school with enrollment of 250 or less, at least five dangerous incidents.

- “For a school with enrollment of 251 to 1,000, a number of dangerous incidents that represents at least 2 percent of the school’s enrollment.

- “For a school with enrollment over 1,000, 20 or more dangerous incidents.”[5]

- Pennsylvania—especially among its low-achieving schools and districts—downplays violence by failing to involve law enforcement and perpetuates violence by failing to arrest violent offenders.

Low-Achieving Public Schools in Pennsylvania

- Pennsylvania public schools that repeatedly score in the bottom 15 percent on standardized tests receive PDE’s designation as low-achieving.[6]

- More than two-thirds (67 percent) of these schools have been low-achieving for six or more years in a row, resulting in kids remaining trapped in a failing school for their entire elementary, middle, or high school tenure and no hope of improvement.

- The 210,962 kids across the commonwealth attending Pennsylvania’s 383 low-achieving public schools are neither safe, nor learning while at school.

Incidents at Low-Achieving Versus Higher-Achieving Public Schools

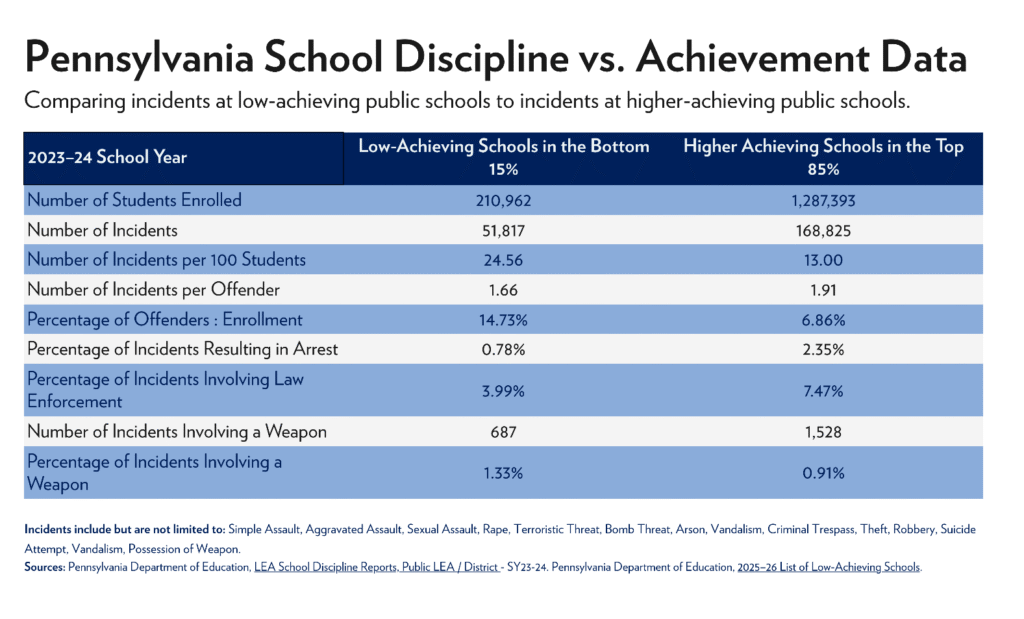

- A review of school discipline data for the 2023–24 school year, as reported by school districts to PDE, shows that students attending low-achieving public schools experience incidents at nearly twice the rate of students attending higher-achieving schools.

- Incidents include but are not limited to simple assault, aggravated assault, sexual assault, rape, stalking, robbery, theft, bullying, suicide/attempted suicide, burglary, arson, vandalism, rioting, bomb threats, terroristic threats, possession of a weapon, etc.

- The number of incidences per 100 students attending low-achieving schools is 24.56 compared to just 13 per 100 for students attending higher-achieving public schools.

- Students at low-achieving schools are twice as likely to commit a violent incident, with 14.73 percent of the student population committing crimes, compared to just 6.86 percent attending higher-achieving schools.

- In both types of schools, the perpetrators of criminal activity tend to be repeat offenders.

- At low-achieving schools, each offender commits 1.66 crimes, while offenders at higher-achieving schools commit crimes at a rate of 1.91 per offender.

- Students attending low-achieving schools are 68 percent more likely to experience an event involving a weapon than students attending higher-achieving schools.

- Weapon offenses at low-achieving schools were counted 687 times, or 1.33 percent of all offenses, compared to 1,528 weapons offenses, or 0.91 percent of all offenses committed at higher-achieving schools.

- Despite the prevalence of violent incidents, school administrators and school safety personnel at low-achieving schools are less likely to engage law enforcement. Meanwhile, higher-achieving schools are more likely to involve law enforcement and arrest students for acts of violence.

- Of the incidents where law enforcement intervened, only 0.78 percent of incidents resulted in arrest at low-achieving schools compared to 2.35 percent at higher-achieving schools.

- The percentage of incidents involving law enforcement at low-achieving schools is 3.99 percent compared to 7.47 percent at higher-achieving schools.

- Acts of violence across Pennsylvania––whether the school is low- or higher-achieving––are committed by 15 percent of students, amounting to 2,215 crimes involving a weapon in just one school year.[7]

- Notably, PDE did not identify any schools as persistently dangerous in its response to RTK data requests for the August report, countering findings in the cited 2024 independent 24-year longitudinal study by researchers at Carnegie Mellon, qualifying 37.3 percent of Pennsylvania district schools as dangerous when measuring incidents with and without arrests.[8]

School Violence Correlates to Lower Test Scores and Poor Outcomes

- School violence impedes learning. Kids can’t learn if they don’t feel safe.

- Hundreds of thousands of kids attend low-achieving, unsafe schools, with the threat of violence a daily reality. The repeated exposure to violence and trauma contributes to inequalities in their education.[9]

- Children facing violence have an increased risk of developing school-related problems, including learning disabilities, language impairments, poor cognitive processing, and poor mental health.[10]

- Across Pennsylvania, the most recent data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows only 44 percent of adults as fully literate, with 27 percent of young adults ages 16–24, in Philadelphia alone, as functionally illiterate.[11]

- The 2023–24 school year data from the School District of Philadelphia evidences the strong correlation between illiteracy and low-achieving public schools.

- The district has 140 low-achieving schools (64 percent of its 218 district schools), educating 61,819 students.

- According to standardized test data, only 35 percent of Philadelphia’s total students scored proficient in English Language Arts, with a more alarming 20 percent proficiency in math.

- Despite the School District of Philadelphia’s four-year graduation rate of 81 percent, many leave school unable to read and write, as evidenced by standardized testing and literacy data.[12]

- Illiteracy among recent high school graduates, moreover, is a national problem. Functionally illiterate young adults who can’t read, write, do math, or speak English fluently struggle to get a job, afford housing, and are more likely to live in poverty.[13]

Pennsylvania is Failing Our Kids

- School district administrators and the PDE are failing Pennsylvania’s most vulnerable students by neglecting to:

- Identify persistently dangerous schools.

- Notify parents that their child attends a violent school.

- Address violence in schools.

- Involve law enforcement when crimes have been committed.

- Provide victims of school crimes with a transfer to a safe school within their district or neighboring school district as required by federal and state law.[14]

- By neglecting to follow and enforce current laws, Pennsylvania risks the loss of millions of dollars in federal funding and perpetuates the poverty cycle by keeping kids trapped in low-performing and dangerous schools.[15]

Policy Solutions

Year after year, Pennsylvania fails to educate at grade level and keep safe the over two hundred thousand students attending the commonwealth’s low-achieving public schools.

The only answer to this complex problem is to offer students trapped in low-achieving and unsafe schools viable alternatives. These include:

- Providing these vulnerable kids a lifeline to attend a private school of their choice. Harrisburg’s current legislative session has two separate but similar initiatives to help students stuck in low-achieving schools with tuition scholarships of up to $10,000: Lifeline Scholarships, in House Bill 1489, and the Pennsylvania Award for Student Success (PASS), in Senate Bill 10.[16]

- The Learning Investment Tax Credit, proposed in HB 1662, offering a refundable state tax credit of $8,000 per student for Pennsylvania families to spend on qualified educational expenses for their children.[17]

- Increasing the access to Pennsylvania’s Educational Improvement Tax Credit (EITC) and the Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit (OSTC) scholarship programs.[18]

Continuing to fund failing public schools by the billions—with no accountability for poor performance or violence—and failing to offer students a transfer out of low-achieving and dangerous schools is no longer an option. The children of Pennsylvania deserve safe schools where they can thrive.

[1] Pennsylvania Department of Education, “Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program (OSTCP) – Low Achieving Schools (2025–26 List of Low Achieving Schools),” accessed October 23, 2025, https://www.pa.gov/agencies/education/programs-and-services/schools/school-services/opportunity-scholarship-tax-credit-program; Pennsylvania Department of Education, “Assessment Reporting,” accessed October 23, 2025, https://www.pa.gov/agencies/education/data-and-reporting/assessment-reporting.

[2] Rachel Langan, “Persistently Dangerous Pennsylvania Public Schools,” Commonwealth Foundation, August 4, 2025, https://commonwealthfoundation.org/research/persistently-dangerous-pennsylvania-public-schools/.

[3] Pub. L. No. 89-10, 79 Stat. 27 (1965); Rebecca R. Skinner, “The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), as Amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA): A Primer,” Congressional Research Service, February 12, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R45977.

[4] 42 Pa. Code§403.2.

[5] 42 Pa. Code§403.2.

[6] Pennsylvania Department of Education, “Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit Program (OSTCP) – Low Achieving Schools.”

[7] Pennsylvania Department of Education, School Climate and Wellbeing Office Discipline Data Repository, accessed October 15, 2025, https://www.safeschools.pa.gov/HistoricV2/Landing.aspx.

[8] Langan, “Persistently Dangerous Pennsylvania Public Schools”; Robert P. Strauss and Hanlu Zhang, “Student Misconduct in Pennsylvania’s Public School Buildings: Evidence from 24 Years of Administrative Records” (Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Mellon University, February 7, 2024), 1, 11, 12, https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/rs9f/rps_hz_2_7_2024.pdf.

[9] Deborah Fry et al., “The Relationships between Violence in Childhood and Educational Outcomes: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Child Abuse and Neglect 75 (January 2018): 6–28, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.021.

[10] Suzanne Perkins and Sandra Graham-Bermann, “Violence Exposure and the Development of School-Related Functioning: Mental Health, Neurocognition, and Learning,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 17, No.1 (2012): 89–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2011.10.001.

[11] Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, “U.S. Skills Map: State and County Indicators of Adult Literacy and Numeracy,” National Center for Education Statistics, accessed October 20, 2025, https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/piaac/skillsmap/.

[12] The School District of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Public Schools: Data for District, Charter, Alternative, and Other/Cyber Students and Schools, “2023–24 PSSA and Keystone – ELA Performance (All Grades),” and “2023–24 Four-Year Graduation,” accessed October 20, 2025, https://schoolprofiles.philasd.org/.

[13] Jessika Harkay, “Many Young Adults Barely Literate, Yet Earned a High School Diploma,” The74, October 16, 2025, https://www.the74million.org/article/many-young-adults-barely-literate-yet-earned-a-high-school-diploma/.

[14] 42 Pa. Code§403.6.

[15] U.S. Department of Education, Guidance letter on the Unsafe School Choice Option to all chief state school officers, signed by Hayley B. Sanon, as principal deputy assistant secretary and acting assistant secretary of the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, May 7, 2025,https://www.ed.gov/media/document/dear-colleague-letter-unsafe-school-choice-option-may-7-2025-109969.pdf; Kyrie E. Dragoo et al., “Federal Support for School Safety and Security,” Congressional Research Service, September 24, 2024, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46872.

[16] Commonwealth Foundation, “PASS/Lifeline Scholarship Program,” May 5, 2025, https://commonwealthfoundation.org/research/lifeline-scholarship-program-pass/; Rep. Clint Owlett, House Bill 1489, Pennsylvania General Assembly, Regular Session 2025–26, https://www.palegis.us/legislation/bills/2025/hb1489; Sen. Judy Ward et al., Senate Bill 10, Pennsylvania General Assembly, Regular Session 2025–26, https://www.palegis.us/legislation/bills/2025/sb10.

[17] Commonwealth Foundation, “Learning Investment Tax Credit,” June 25, 2025, https://commonwealthfoundation.org/research/learning-investment-tax-credit/; Rep. Martina White et al., House Bill 1662, Pennsylvania General Assembly, Regular Session 2025–26, https://www.palegis.us/legislation/bills/2025/hb1662.

[18] Commonwealth Foundation, “Record Tax Credit Scholarship Waiting List Shows Growing Demand for Education Options,” February 26, 2025, https://commonwealthfoundation.org/research/tax-credit-scholarship-waiting-list/.